***Warning: this article contains spoilers***

This week Denis Villeneuve’s long-awaited cinematic adaptation of Frank Herbert’s seminal novel Dune has finally been released in UK cinemas. Way back last year, when the original trailer was released, and before the film’s release date was pushed back to October 2021, we wrote a brief opinion piece on how the film looked like it was shaping up. Now that we have seen the full feature, it is time to revisit that assessment in full.

Before we get into the analysis, I should go on record as being a big fan of the original 1984 Dune. Yes, it has deep flaws on multiple levels, and yes, even director David Lynch himself disowned it, but I first saw the film at a relatively young age, long before I had even heard of the novel upon which it is based. The themes, technology, music, and characters of the film all struck a chord with me that continues to this day. I rewatched the film so many times in fact that I’m a little embarrassed to admit that I struggled to get into the novel for years. Even minor differences were jarring to me. Fortunately, I eventually got over that issue and ended up devouring the book as I came to appreciate its greatness independently from the film. Although I will always love the 1984 film despite its issues, I also adore the book. I have matured past the struggles I had with comparing and contrasting the novel and the original film adaptation, and appreciate each of them for what they are. Furthermore, I have seen Dune 2021, and it is a masterpiece of cinema. So how do they all compare, really?

The immediate elephant in the room is the fact that a complete cross comparison still cannot be done because the 2021 film is only half the story, that is the full 2021 film covers only half of the source material and half of the 1984 film. For those familiar with the novel, Denis Villenueve’s Dune (specifically subtitled: Part 1) ends a little over halfway into the second act, Muad’Dib, not long after Paul first encounters the Fremen in the deep desert. Therefore, this cross comparison will be ignoring any events that occur after that point.

Covering only half the source material enables Dune 2021 to fully embrace it. A major issue with the 1984 film is that, even with a runtime of over 2 hours, it tried (and arguably failed) to compress too much source material into a feature-length film. This inevitably meant that a number of scenes in the novel had to be cut and some characters sidelined, most notably Duncan Idaho. The 2021 adaptation does not suffer as badly. By only presenting the events up until the novel’s midpoint, and benefiting from a slightly longer runtime, the new film has much more room to breathe. It includes more events from the book and is a more faithful adaptation. It is still missing some scenes of course, such as the wet-planet conservatory and the Atreides defence and counter attack against the Harkonnen invasion of Arrakis, led by Thufir Hawat, but these are not so important to the overall narrative and are understandable omissions. Nonetheless, they could still turn up in a future director’s cut. Missing scenes aside, both films still hit all the key scenes that form the backbone of the story within the book. Dune clearly does a superior job in terms of presentation, narratively and visually, but the 1984 version should still be respected for putting the right scenes on the screen, even if they’re not 100% faithful due to the need to constrain them. Despite the need for compression of the narrative, David Lynch did fabricate some of his film’s initial scenes. The Padishah Emperor’s meeting with the Stage IV Guild Navigator that forms part of the introduction, does not appear in the book. As fascinating as this encounter between political royalty and a psychic pink slug floating in a gas tank is, the latest incarnation proves that this scene was unnecessary.

The real advantage that the breathing room gives the 2021 film over the 1984 version is how exposition is handled. The exposition in the original is infamously clunky, and impenetrable to some. It could easily be argued that this was at the core of its critical disdain. Even the studio had no faith in how the film presented itself; theatre audiences were supplied with handouts that aimed to alleviate confusion by providing a guide to the key terminology and factions. Fortunately, Villeneuve expertly handles exposition by feeding the audience just the right amount of information at the right pace. It truly is a masterclass in script writing. One thing that the previous Dune does get sort of right however, and which the new film does not feature, is the historical documentary by Princess Irulan that frames each chapter in the book and is translated into narration for the original film. The princess is completely absent from Dune, but this is no great surprise as she doesn’t actually appear as a character within the story herself until the novel’s conclusion. Exposition that was formerly delivered by Princess Irulan is instead now partially provided by the character of Chani (Zendaya). Although this isn’t exactly faithful to the text, it’s not in conflict with it either and is one of those elements that is open to artistic licence.

Dune has a large cast of strong characters, though the two films choose to focus on them differently. Of course Paul is front and centre in both films. Although confused by his visions, Kyle MacLachlan’s Paul is bold and mature and is a character that you can easily rally behind. Timothée Chalamet’s Paul perfectly embodies the paradoxical simultaneous confidence and self-doubt of youth that is consistent with the character within the book. Confusing visions also plague this incarnation of Paul, but Chalamet portrays the character’s internal conflict more effectively, which is also aided by a superior script to work with. A key scene for Paul is the box test that requires him to place his hand inside a simple box that bestows pain upon him. If Paul removes his hand prematurely, Bene Gesserit Matriarch Giaus Helen Mohiam will kill him with a poison needle. Both films play out this particular scene well, complete with symbolic imagery and a tense atmosphere. I was impressed with both versions of this scene; MacLachlan and Chalamet each deliver it effectively and show the audience a significant element of Paul’s character. The constrained nature of Lynch’s work however, limits our ability to understand Paul, whilst Villeneuve gives more opportunity, highlighting further insights into Paul’s visions. A great example of this is the war armada across the universe that does not appear at all in the original film, but is a cornerstone of Paul’s troubles in the book.

Supporting the character of Paul is the extended Atreides family and their staff: Duke Leto, Lady Jessica, Gurney Halleck, Thurfir Hawat, Duncan Idaho, and Dr Yeuh. We covered visual appearances in our previous article and won’t retread old ground here, and will instead focus on their roles within the respective films. In my opinion, both films portray these characters faithfully, yet understandably, the new Dune gives more time to each of them, allowing them to appear in more scenes that align with the book. One point I did pick up on particularly, concerns the early introductory scenes for these characters. The 1984 Dune introduces Paul, Gurney, Thurfir, and Dr Yeuh together in a single scene; in the book this plays out as separate encounters between Paul and each of his mentors. The 2021 Dune replicates this, except Thurfir’s scene is absent. It is undoubtedly Duncan Idaho however, who has the most substantial difference between the two films. Duncan was previously a very minor character, essentially a glorified extra, but now he is fully present and it was great to see the authentic conclusion to his story arch. Only one reasonably significant scene for Duncan is still missing however, in which he is found drunk and disorderly in the great hall, despairing over his disillusionment with their new home. An incident that almost gets him court-martialled. Already noted is the absence of Thufir Hawat’s counter-offensive of the Harkonnen attack on Arrakis, Lady Jessica’s water garden (in both films), but otherwise the Atreides cast of characters get all the right scenes. It was particularly great to see Paul get more scenes with his parents, which highlighted their bond and tribulations.

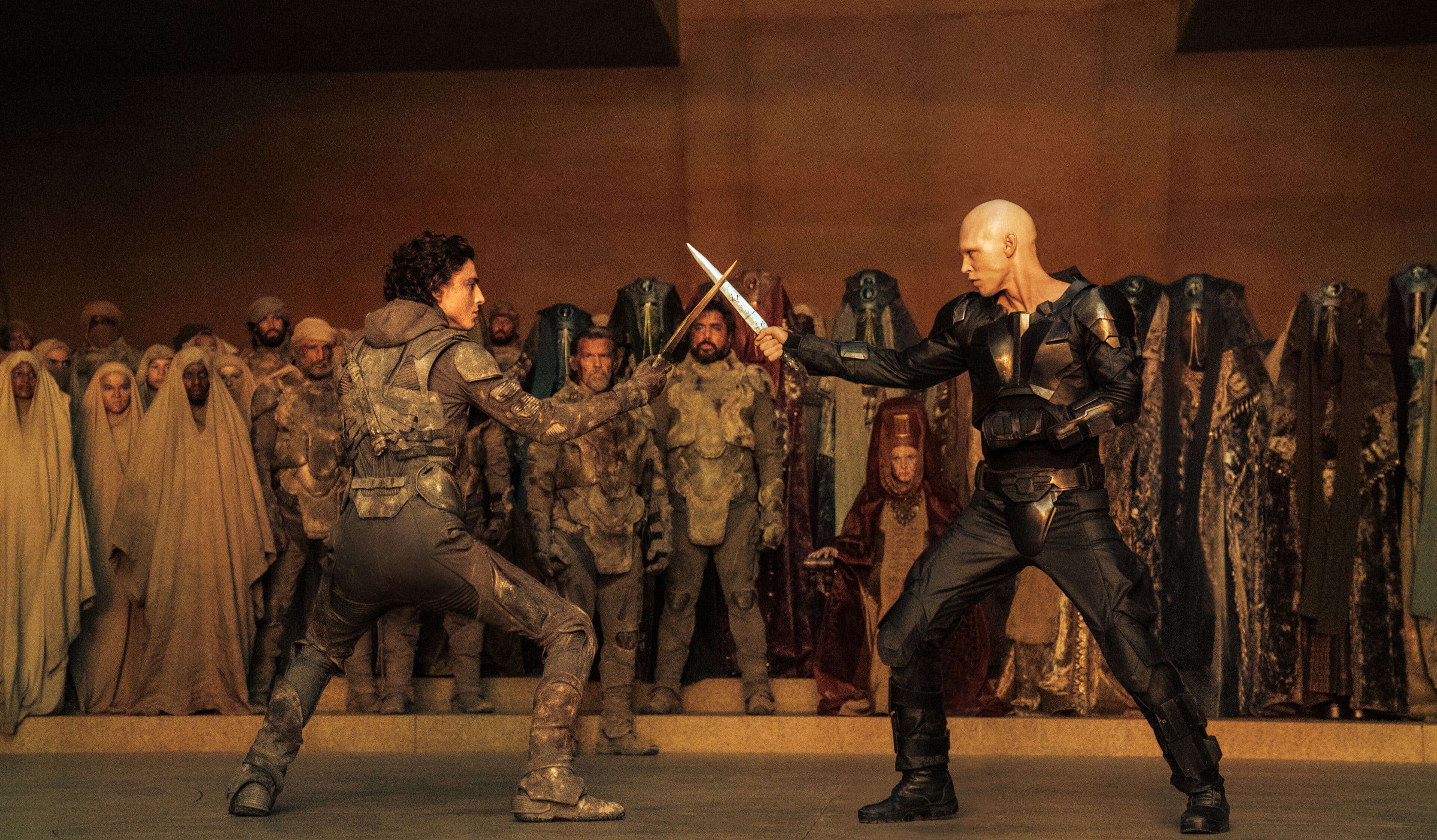

The Fremen feature very differently across the two Dune films. Considering that Villeneuve’s version only covers the first half of the book, it automatically has a big advantage over Lynch’s film by including them at all. In the 1984 film the Fremen don’t appear until it’s midpoint (shortly before where 2021’s version ends), but as the new film highlights, they actually appear almost as soon as the Atreides reach Arrakis. Immediately Paul is openly referred to as the ‘Lisan Al Gaib’ (messiah) by the city residents (of which some are reportedly Fremen); Paul is acutely aware of his impending destiny from early in the story, something that the former film side-steps, and the newer film nails. In addition to this, Paul encounters the Fremen multiple times before finding them in the deep desert. The new iteration correctly presents the first time Paul meets Stilgar, and reveals that Leit Kynes is a member of the Fremen, although the new film does not highlight quite how revered Kynes is within the Fremen community and that she (or he) is their leader. One may note that Kynes is visually very different here to that of the book and the original film, but that of course doesn’t matter. Finally, for the Fremen, this version features the fight between Paul and Jamis that enables Paul to be recognised as a worthy member of the tribe. He doesn’t get a free pass like he did in the last movie.

Next we come to the Harkonnens. The Harkonnen’s appear very different in each film: they are notably ginger in Lynch’s Dune, and bald in Villeneuve’s Dune. The book does not describe their hair colour at all, although it is possible that they were originally made to be ginger to represent an unspoken twist that is revealed in the book, but not in either film – it should have been revealed during the events of Dune 2021, but it may be reserved for its sequel so I shall not spell it out here. David Lynch’s Dune had the Baron Harkonnen as a hideous and obese man with horrific skin disease that made him uttery repellant to look it, but in the book he is simply grotesquely obsese rather than grotesque and obese. The latest interpretation is visually more faithful to the novel. Having read the book, I wonder whether David Lynch’s decision to present the Baron the way that he did was to visually represent his monstrous personality. In the book, the Baron is, amongst other things, a rapist, and a particularly grim one at that. Understandably (and fortunately), this is not something that the Villeneuve version features either. Those that have seen both films, but not read the book may be confused by the absence of the character of Feyd Rautha (Sting’s character in Lynch’s film) in the new movie, but this is to be expected as he does not appear in the book (at least in person) until after its midpoint.

There are many great things about the universe of Dune that go beyond the characters that inhabit it, that make it rich and compelling, from fauna to technology, culture to politics, religion to psychic abilities. There is so much to dig into that it’s a challenge for any film to present them on screen. As significant as sandworms are, they have been discussed previously, so I won’t dwell on them again here. Instead I want to highlight some aspects of the films that were not shown in the trailer, and how both films have interpreted them. First up is space travel. In the Dune universe, faster than light travel through space is achieved by folding space (although this isn’t explicitly mentioned until the sequel novels to Dune) – moving without moving – which is facilitated by enormous heighliner spaceships operated by the Spacing Guild. Both films accurately feature these enormous vessels that can transport hundreds, if not thousands of smaller ships. They do, however, present them differently. The original has heighliners that fit the traditional concept of a transportation vehicle that holds smaller ships inside its bowels like a gigantic space ferry. In contrast to this, the heighliners now appear more like gateways; tunnels through space. Both concepts look awesome, but I would argue that it is the original movie that is more accurate against the book in this case.

Moving on from technology, an intriguing capability within the Dune universe is the voice. A hallmark ability of members of the Bene Gesserit sisterhood, the voice enables well-trained individuals to compel other people to act against their will; it’s akin to the ability of compulsion used by vampires in horror fiction, though not quite so dramatic. It features in both Dune films as it is a core component of some key scenes and there is not much to distinguish between how it is represented; both films do it justice. Nonetheless, it was interesting to see more considered discussions of its delivery and application this time around. Another infamous Bene Gesserit ability is the Weirding Way, which is a specific element of hand-to-hand combat that enables those who have mastered the skill to move at incredible speed and precision. The underlying concept of this ability involves manipulating perceptions to achieve a sense of short distance teleportation. We were especially excited to see how this would be presented in the new Dune film, in part because it was changed before. In the original Dune film, the decision was taken to change the concept of the Weirding Way to the manipulation of sound. This was delivered in the form of sonic weapons used by the Atreides and took it away from the Bene Gesserit, which goes completely against the book. It is odd that Lynch does still reference the Weirding Way when Paul and Jessica first encounter the Fremen, even though the ‘Weirding Modules’ are not used. It is this scene where the Weirding Way is supposed to be introduced, so how did the new film handle it? A lot of fancy close-shot camera work and editing provided a sense of fast movement, but there was no true sense of teleportation. Perhaps that is not a direction that Denis Villeneuve decided to go in, but then again the weirding way is manipulation of an opponent’s perception and, as the audience, perhaps we are unaffected and therefore not privy to observing that teleportation directly. The Weirding Way should feature more in the (hoped for) sequel film, so let’s wait and see what further happens with it. Nonetheless, Dune 2021 unquestionably is more faithful to the novel than Dune 1984 in this regard.

We have considered many different elements of the films and the books here. Aside from some minor adjustments and contrasting artistic interpretations, without a doubt, Villeneuve’s Dune is far more faithful to the novel than the original 1984 film. This new Dune should be commended as a brillant cinematic adaptation, even more so given how challenging that process is known to be, which makes the feat all the more impressive. Having said that, Lynch’s attempt still managed to get a reasonable amount right and it will always be a nostalgic and special film for me personally. Dune 2021 however is a powerful and awesome addition to Dune history that, although surpasses the original film, does not replace it for me. Instead it strengthens my appreciation of this epic piece of science fiction.

Dune is in UK cinemas now.

Latest Posts

-

Film Trailers

/ 16 hours agoM. Night Shyamalan’s ‘Trap’ trailer lands

Anew experience in the world of M. Night Shyamalan.

By Paul Heath -

Film News

/ 1 day agoFirst ‘Transformers One’ teaser trailer debuts IN SPACE!

The animated feature film is heading to cinemas this September.

By Paul Heath -

Film Reviews

/ 1 day ago‘Abigail’ review: Dirs. Matt Bettinelli-Olpin & Tyler Gillett (2024)

Matt Bettinelli-Olpin and Tyler Gillett direct this new horror/ heist hybrid.

By Awais Irfan -

Film Trailers

/ 1 day agoNew trailer for J.K. Simmons-led ‘You Can’t Run Forever’

A trailer has dropped for You Can’t Run Forever, a new thriller led by...

By Paul Heath