Steven Knight is better known as a writer and it’s his first love. Most recently penning TV’s Peaky Blinders, as well as Taboo, he’s also been on screenwriter duties for films including Allied and The Girl In The Spider’s Web. But occasionally a story will exert such a hold that he’ll direct it as well. Locke was one, his latest, Serenity, is another.

A film that’s already divided the critics, its plethora of movie references make it a must for movie geeks. Film noir gets pride of place, especially in the form of Anne Hathaway’s bleached blonde femme fatale, persuading fishing boat owner Matthew McConaughey to help her kill her husband. And she’s prepared to pay a high price for her freedom. That’s only half the story, with the latter stages of the narrative including a twist that would make even M Night Shyamalan raise an eyebrow.

Talking to THN’s Freda Cooper, he reflects on working with other directors and what he’s learned from them, why he believes McConaughey is today’s Robert Mitchum and why he likes to mix things up just a little bit.

Read the interview in full below.

It’s quite an extraordinary film, so where did the idea come from?

I write a lot of conventional films for studios – credited and uncredited – so I’, completely familiar with the three-act structure and the character arc and all of those rules. People think you cannot break them but if I’m going to direct a film, I tend to pick a project that comes to my mind that I know if I handed it over to the system it would get changed. Like Locke. If I had handed that over I’m sure there would be a lot of pressure to see other people. With this, if I had handed it over, it would have never been executed in the way it is, which is how I wanted it to happen. What I wanted to do was to create a sort of heightened, conventional film and then disrupt it at the most inconvenient moment and break most of the rules. The story came as a result of being on a fishing boat a few years ago in St. Lucia. The captain of the boat took tourists out and he was great, and he was fine. He brought you a beer until a fish bites, and then he was obsessed – you didn’t exist. He took the rod – it didn’t matter.

Which is exactly as you see in the film.

Exactly. I went out a couple of times with him and it was always the same. I talked to people about him and they said ‘there’s a fish he wants to get’. It rang the bells of Captain Ahab and all of that, so, what I wanted to do was create a fishing captain who was an archetypal, American male hero, which is dislocated, out of place, closed down with secrets, adrift on the void. A bit like Clint Eastwood on the prairie. He’s out there, he wants to catch this fish and has no interest in anything else. Then [I wanted to] set-up this conventional movie scenario – a femme fatale coming in and offering him this temptation – do all of that – get that car on the road and smash it into a tree, and then just one wheel going down the road and see if you could do it. Doing the conventional thing is great – it’s fine but if I’m directing something I don’t see the point unless you’re going to do something different.

You mentioned the femme fatale there – very much in the tradition of Lana Turner, Barbara Stanwyck – very much in that mode. How much did you want to do a homage to film noir? Are you a big fan of that genre?

I sort of am. What I’m less keen on is the whole idea of genre being the defining influence on a film. Again, as with the other rules, in order to market a film you have to say what it is – it’s a thriller, it’s a comedy – and I think the noir genre, if there’s any genre I’m drawn to, it’s that and we obviously all grew up watching TV – watching those fantastic movies, which interestingly now, they’re a genre that’s very established, but at the time, they were quite revolutionary. They were hard-bitten, realistic, sexy, pushing the boundaries films. But I wanted to pick a genre and then take it away.

Then, of course, there’s the other side of the story, which you mentioned – about disrupting it. Where did the inspiration from that side of things come from?

Watching my kids play computer games, I’ve become convinced that the suspension of disbelief, when someone plays a computer game, is more profound than the suspension of disbelief when they watch a film. Because they are involved in it. It looks to me, when I see my kids playing a game, that there is the screen there with the cues and the prompts that the game provides – the graphics are not that great, but there is a screen between them and the screen in which they are creating a reality that is partly in their head, but they are viewing it as if it is a new reality. You walk into a cafe or a bar now and there are twenty people looking at screens and they are not really in the bar anymore. They are in there [the screen] as well. So that reality and this reality are parallel. If you tap someone on the shoulder they will be half and half for a little while, but what I wanted to do was take that phenomenon and use it to explore existentialist ideas of what is reality. The point of the ending is, the reality that is created by the boy is as real as the prison cell he’s sitting in. That’s the point.

Directing isn’t something you do that often. We know you much better as a writer. How did you combine the two roles? Are they two separate roles for you? I ask this of every writer/director that I meet. Is there a dividing line or do they merge?

For me, the reason for deciding to direct a particular project is because you know the script itself would otherwise get completely changed. Because of the nature of it. Because you know it is going to be controversial. Because you know it is going to be difficult. So that’s why I want to direct it in the first place. When you write, again it’s looking at a screen and a keyboard but you’re seeing what you’re writing. You’re seeing it somewhere, somehow, and when you direct you want to try and get it as close to that as you can. The horrible lesson that you learn on day one when you’re directing your first film is that this is the real world, and it’s got problems and snags and things, and bodies and actors. The big compromise is that it’s not going to be what’s in your head, but I think you can try not to compromise on the script. If there’s a situation where you think it’s not working, you can change it, but I try, where possible [when directing] to keep the script intact.

You’ve got Matthew McConaughey and Anne Hathaway in the two leading roles. Why them?

Well, with Matthew, if you’re going to create that all-American hero archetype – he’s the Robert Mitchum of our day, in my opinion. He’s got that closed-down, unavailable presence. He’s sort of irresistible. People are still knocking the door that’s locked, trying to get in, and that’s what you want. Anne, I think, is the best actress around and so they were both first choices. In that mysterious way that things happen, they got hold of the script, read it and they were on board.

Just going back to you being a writer primarily, the film’s that you’ve done have been directed by some pretty heavyweight directors. Robert Zemeckis, for example. I wondered what you picked up from them on the way. Were there any words of advice?

They are all different and they all teach different things. They’re all great characters and quite funny even when they don’t know they’re being funny. For example, James Mangold said ‘if you get a good take, do it again but quicker [laughs].’ Frears always used to say ‘that was perfect. One more.’ Cronenberg was so precise and had such a regimented day and keet control, which was really, really good. They all offer something different but the main thing that you learn from the best directors is ‘get the best people and let them get on with it.’ As opposed to trying to control every department. If they have an idea, as long as it’s within reason, then let them carry on.

Most recently, in terms of your writing, there was The Girl In The Spider’s Web, which is different again because this time it’s an adapted work. It’s not an original one for you and it’s part of a franchise. What sort of challenges did that present you with?

You have two lives -well, you have many lives – but on of them is the studio adaptation business and it’s something I do sometimes credited – sometimes not, which is fine -that’s not a complaint, by the way. It’s the system, it’s fine. With that system, you do your bit, you hand it in, and then the director and another writer perhaps, will take a look at it and then it will go on to the next stage and then it will get made. That is the studio system that works perfectly well, but it’s the system that if I want to do something that I am personally very attached to, I’ll try to avoid allowing it into that.

Would you see yourself getting into another big franchise?

Absolutely. I think it’s fun. I always try and make the next project as different from the last one as much as possible so, if a franchise comes along, why not? I’ll give it a go. It’s all part of exercising the same muscle.

So what else have you got coming up?

I’ve got a thing being shot for Apple at the moment in Vancouver. I can’t talk about it, but it’s got Jason Momoa [in it]. I’ve just finished writing A Christmas Carol for the BBC. I’m going to be doing five more Dickens novels over the next seven or eight years.

That’ll keep you busy. Which ones?

I love it. I think David Copperfield, Oliver Twist, Great Expectations – plus one.

Following in David Lean’s footsteps.

I love it. A Christmas Carol will be such fun.

That’ll be the difficult one as there have been so many adaptations.

You can’t match The Muppets, I’m afraid.

I’m not going to disagree with you on that.

We’ve also just finished shooting series five of Peaky [Blinders], and I’m writing series six. I’ve done six of the eight Taboo, so two more to do. Then we’ll be shooting Taboo, and then a film called Rio, which I wrote, which I hear is getting shot this year.

Plenty to keep you busy.

Yes.

Thank you so much for your time.

Serenity is released in cinemas and on-demand on Sky Cinema on Friday 1st March.

Latest Posts

-

Film News

/ 9 hours agoFirst ‘Transformers One’ teaser trailer debuts IN SPACE!

The animated feature film is heading to cinemas this September.

By Paul Heath -

Film Reviews

/ 9 hours ago‘Abigail’ review: Dirs. Matt Bettinelli-Olpin & Tyler Gillett (2024)

Matt Bettinelli-Olpin and Tyler Gillett direct this new horror/ heist hybrid.

By Awais Irfan -

Film Trailers

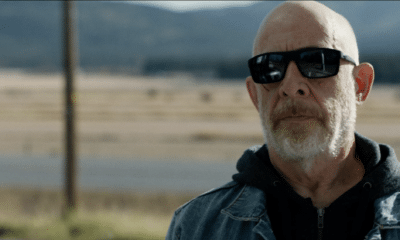

/ 10 hours agoNew trailer for J.K. Simmons-led ‘You Can’t Run Forever’

A trailer has dropped for You Can’t Run Forever, a new thriller led by...

By Paul Heath -

Film Trailers

/ 15 hours agoNew trailer for Shudder’s ‘Nightwatch: Demons Are Forever’

Coming to Shudder this May.

By Paul Heath