Jason Reitman admits he’s too young to remember the real events that inspired his latest film, The Front Runner. He was still in short trousers when Senator Gary Hart campaigned to be the Democratic candidate in the American presidential election of 1988 – a bid that lasted all of three weeks and catastrophically ended in scandal.

The Front Runner

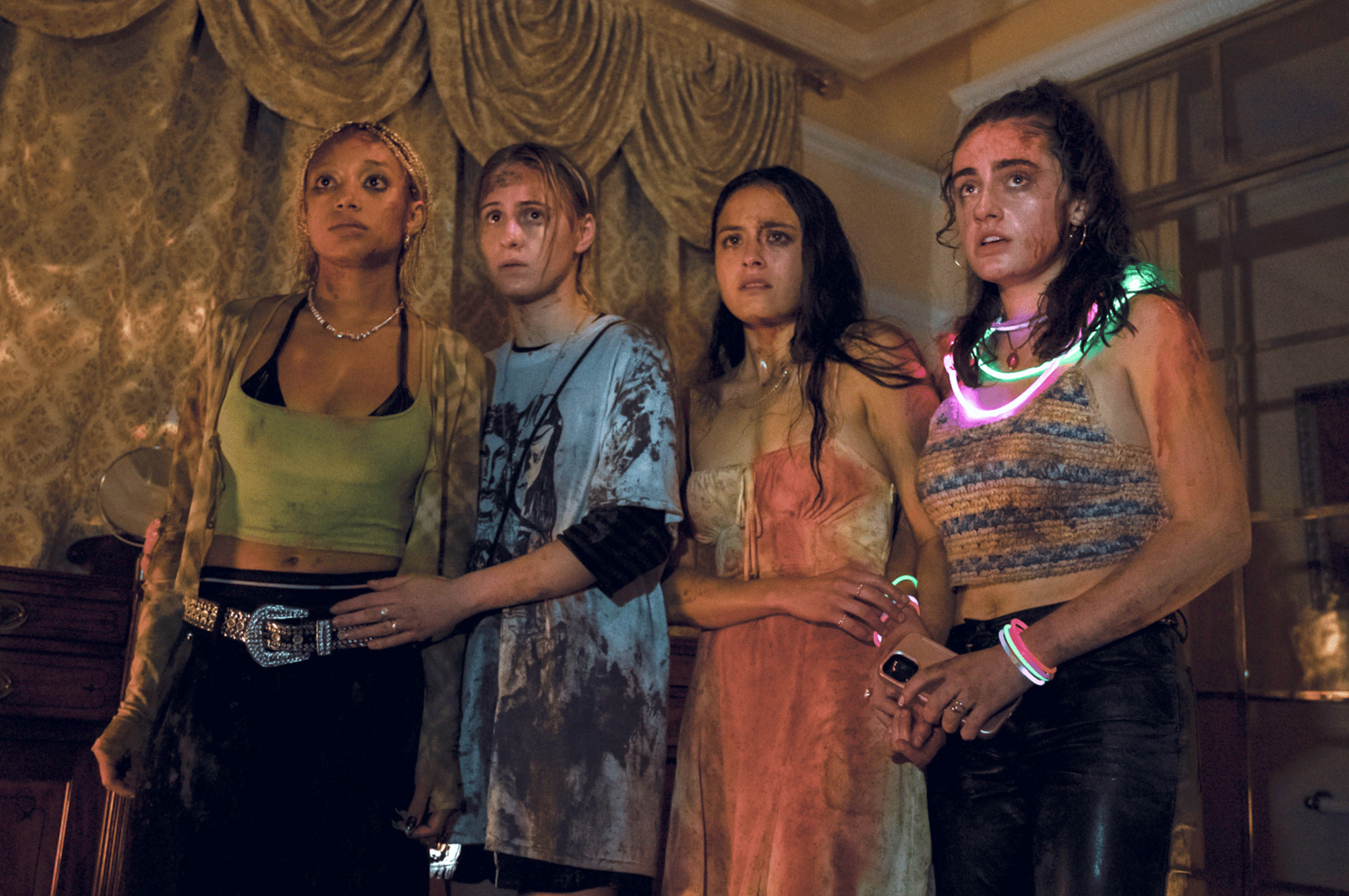

The movie, which received a gala screening at this year’s London Film Festival, also proved something of a favourite at TIFF last month. With Hugh Jackman as Hart and a supporting cast that includes Oscar winner J.K. Simmons and Vera Farmiga, the film is already causing some major awards buzz. Reitman sees what is his second film of 2018 (the first was Tully), as an antithesis to the slick politics of The West Wing – and is adamant it’s just as much about its two female characters, Hart’s wife Lee (Farmiga) and Donna Rice (Sara Paxton), with whom he was accused of having an affair, as it is about the presidential candidate himself.

As for what he believes the film has to say about present day American politics, just read on …..

It’s not a story that not that many people know about – about Gary Hart. Was that part of the appeal for you?

Jason Reitman: Well, I didn’t know the story.

You’re probably not old enough.

I was ten years old when this happened and I knew the names, but it was a year of scandals. It was the same year as Tammy Faye Bakker and Oliver North in the U.S.. In 1987 I was more curious about where the Back To The Future trilogy was going and it wasn’t until I heard a podcast a few years ago that described the story that I felt as though this was, one – a movie I need to tell, and two – it seems to answer, or at least raise questions about how we go to 2018.

So, what made you feel that way about the story?

Well, it was cinematic in its telling. Here you had the next president of the United States in an alleyway in the middle of the night with three journalists trying to figure out what to do. No one has ever been there before, and then within a week, the next president of the United States leaves politics forever. It was like a western stand-off in a film noir. It just feels like a movie. Beyond that, I’m like anyone else alive today. I look around and I wonder how the hell did we get here, and here was a story that in its DNA asked questions about gender politics; it asked questions about the line between your public and private life; it really was thoughtful about the relationships between journalists and politicians.

So, in terms of getting here, what do you think it has to say to us about American politics now?

Well, it says a lot about our curiosity and what we find entertaining and what we find relevant. We are at a point when we have a completely indecent human being as our president and his choices and mistakes have become so outlandish that we can’t even process them anymore, and they seem to follow a trend of our curiosity into the actual personal lives of these people that take is away from their ideas. So, I’m interested in that balance – how do we understand what people stand for and simultaneously understand who they are as people. I wanted to get out of the shrill Twitter conversation of 2018 and get to a place where you could actually have a conversation and Gary Hart serves a very interesting test case.

Social media didn’t exist then, it was just telephones and typewriters.

Yes, and we go from a moment in which we never ask questions that are genuinely important to a moment where we always ask questions about their personal lives. We have to remember that sex is a white-hot topic. We talk about sex, we don’t talk about other things, so it is relevant, but there has to be space in the conversation for other things as well.

Related: The Front Runner review [TIFF]

The opening sequence in the film is such an assault on your ears because everyone is talking. You can’t distinguish one conversation from another, until in narrows down to the people around the table. I want to talk about directing that one particular scene because, if nothing else, it struck me as the antithesis to the slickness of The West Wing.

Thank you for saying so, and that is exactly what we were going for. There is a specificity to [Aaron] Sorkin who is telling you exactly what to look at and telling you exactly what to think, and we wanted to make a movie…

You don’t know with that scene…

No, and from moment one we wanted to establish very clearly with the audience that there is no way to listen to everything in this movie, and there is no one opinion. We are going to be overlapping three conversations at once, some will be relevant, some will be completely irrelevant. Your ears will go places before your eyes, and it will feel as if you just got dropped into the midst of a campaign, and are trying to catch up. You will have to answer the same question that we were posing philosophically, cinematically – what do you want to look at; what do you want to listen to; what is relevant?

Obvious question, why Hugh Jackman?

[Laughs] Why not Hugh Jackman? He’s such an incredible movie star in that his talent is only surpassed by his decency, and he’s has hard-working as anyone I’ve ever met. He’s some who, the first one we met him said, ‘I never want to feel that I could have done more.’ That is an inherent truth to that man.

He has such a range as an actor.

Oh yes, whether he is murdering people with his claws or dancing, or singing, but in this movie, he clearly does something very different, and that was the challenge that we were both excited about – the idea of playing a character who is an enigma – someone we are desperately trying to understand that won’t let us through the door. I think that’s the way people have felt about Gary Hart, even his family and his friends.

This one you wrote, and you directed, and that’s something you frequently do…

This one was co-written, and there’s no way I could have made this movie without my co-writers – one was a New York Times magazine writer over five presidencies, the other had been the press secretary for Hillary Clinton and Howard Dean, so this was a movie written from the perspective of people who have been in the trenches for the last twenty years, and we are filling the details of this film with their personal experiences.

So, when you direct and write a film, are they two processes that merge, or do you keep them completely separate? I have asked this question to so many different directors and they’ve all got a different answer.

For me, they are one and the same. I feel that there’s a story to be told and the visual ideas come to me very early on and we create this blueprint in the script that is a bit of the dance instructions. Then you get set and its this continuation, and on this movie, it was a whole new thing for me. We were trying to create something alive and messy, so we were giving the opening instructions but it was impressed on the crew and the cast to take it and run with it – to create a room that is always surprising ourselves.

I’ve read that you’ve been quoted in saying that you like to tell original stories and that means stories about women. Now, Tully – women’s story. On the face of it, this is a story about a man, but I was also wondering how much it was about the two women, particularly Donna Rice.

I think that this is a women’s story. I’ve worked with the same producer, Helen Estabrook, since Up In The Air, and I think, on that movie, early on, she was challenging me ‘what is the women’s story here – what is the relationship between George Clooney and Anna Kendrick – what is the relationship between George Clooney and Vera Farmiga?’ That continues to this day. She would challenge me every day on this film to think about ‘what is the emotional burden’ – her words, not mine, and very smartly said – ‘what is the emotional burden that is put on the shoulders of women in the midst of a scandal that is different from a man?’ She would challenge me to that, every day, whether we are humanising, and giving decency towards Donna Rice, or thinking about Vera Farmiga, as Lee Hart – the woman in the midst of a scandal – who is not shrill, whose anger is contained, who is thoughtful about her approach to her marriage, or frankly, Irene Kelly and Ann Devroy, characters at the Post and on the campaign – women who, as Helen would put it, are forced to speak for their entire gender.

The Front Runner was screened at the BFI London Film Festival on 14 and 15 October and is released around the UK on 25th January 2019.

Latest Posts

-

Film News

/ 48 mins agoUK trailer, poster and release date for Sundance smash ‘Sasquatch Sunset’

Premiering in the UK at the Sundance London event in June is the brilliant...

By Paul Heath -

Disney+

/ 2 hours agoNew trailer for ‘Becoming Karl Lagerfeld’ with Daniel Brühl

A trailer has landed for the June-released Becoming Karl Lagerfeld, the Disney+/ Hulu series...

By Paul Heath -

Film News

/ 2 hours agoUK release date revealed for Cannes film ‘The Delinquents’

MUBI has announced the release date for The Delinquents, the Cannes Un Certain Regard-premiering...

By Paul Heath -

Film Trailers

/ 2 hours agoA new trailer for ‘Star Wars: Episode I – The Phantom Menace’ ahead of re-release

The first prequel is back in cinemas next week.

By Paul Heath