Director: Pierre Salvadori

Director: Pierre Salvadori

Cast: Audrey Tautou, Nathalie Baye, Sami Bouajila, Stéphanie Lagarde

Certificate: 12A

Running Time: TBA

Synopsis: 30-year-old Emilie runs a hairdressing salon, and provides an endless stream of well-meaning advice to her clients and friends…

Sadly the one person she can’t seem to help is Maddy, her mother, who has given up the will to live since being left by her husband.

Jean, a young man who works for Emilie is secretly in love with her but a pathological shyness prevents him from declaring his feelings. Finally, unable to contain himself, he opens his heart in a passionate anonymous letter.

Entirely untouched by this confession and terrified to see her mother slipping deeper and deeper into despair, Emilie concocts a crazy plan: she’ll change the name at the top of the letter and send it to Maddy.

Deeply touched by this beautiful declaration of love, Maddy rediscovers the will to live and begins to watch for the mail. While she’s over the moon to see her mother returning to life, Emile is fully aware of the problems that lie ahead. Not only must she supply Maddy with more love letters, she must also find someone willing to play the author…

Directed by Pierre Salvadori, Beautiful Lies is an endearing story treating the mother-daughter dyad, carved by the whimsical and charismatic performances of pretty Audrey Tautou (Emilie) and delightful Nathalie Baye (Maddy). We are transported to the temporate climes of Southern France, away from the Parisian frenesie that defined Tautou’s Amelie, and to the central locus of the plot, Emilie’s provincial hairdressing salon and parlour of image. The premise of the film basically resides in the themes of identity, self realisation and ultimate self perception/knowledge: a mirror’s reflection (the coiffeur’s weapon of choice with which she confronts each of her ‘victims’), ourselves as we are perceived by others, a mother’s gaze and a lover’s gift of self validation.

The sense of ‘otherness’ abounds when we witness handyman Jean (Sami Bouajila) and his timid attempts to win unsuspecting Emilie’s heart when he pens an anonymous love letter to her. The written word and theme of creativity prove intrinsic to the script as a beautiful trail of cause and effect unfurls. Well meaning and forthright Emile decides to console her abandoned mother by retrieving Jean’s emotional outpouring from the waste paper basket and re-scribing the letter for Maddy. Unable to let go of her cheating ex husband, Maddy presents herself as a wretched, love-forlorn figure craving the sweet fruits of Jean’s love for Emilie: an intense, beautiful love highlighted by the poignant overlap/duet of both Emilie and Jean’s voices during the scene in which we see Emilie typing Jean’s words.

As the camera pans from the sky and hovers above the bustling crowds like destiny, we see the transformation afforded to mother by daughter. Maddy radiates a new lease of life: her confidence and happiness is reflected in her yellow shirt and luminous smile as we see her bound along with coquettish zeal. Emilie perceives how happy her mother appears and decides that she must keep sustaining her mother with these letters. Love, like sugar nourishes us much as a mother nourishes her child. Here, however we also perceive the inverted theme of child bringing meaning and identity to the mother.

The emotionally contained Emilie is flanked by the ebullient emotions of her creator (Maddy) and the intense emotional desire of her suitor (Jean). Set in direct contrast to Maddy’s comical chaos and Jean’s farcical Gallic turmoil, Emile is a tough cookie, a capable and practical daughter, well attuned to the whims of her unstable mother. When she is faced with playing ‘creator’ however, composing her own fake love letter to continue this elaborate gossamer of mensonges, Emilie hits the vodka bottle and relies on alcohol and not art to abandon her inhibitions to connect with her true Self. In this witty scene of role play, we see Emilie shed her identity as daughter, possibly a nod to the actress’ role to assume another identity and ‘get into’ the part.

The theme of words and semiotics appears in a fantastically funny scene where Emilie mixes up the words ‘Maddy’ and ‘Mami’ when alluding to her mother’s ‘proud breasts’, again centring our attention back to the principle focal point of identity. Emilie is trying to assume the role of an imagined lover to Maddy, but inadvertently utters the similar sounding word for Mummy: a glaring Freudian slip that screams self perception being the creation of the ‘other.’ A child relies on a mother’s breast and gaze to nourish their growing sense of self much as a lover’s identity is reliant on a reciprocated love. It is this mutual exchange and notion of symbiosis which again invites the audience to consider the meaning of art as a construct, shaped and bestowed with meaning by the spectator.

The shifts in language and self/other relations are similarly echoed in the transition and transformation of the film’s characters. Maddy ‘sheds the pain of her past,’ literally divesting herself of her clothes in her various states of undress as her character grows stronger and more confident with every amorous proclamation. Jean equally excavates a stifled assertive self and galvanizes himself as Emilie’s steely façade crumbles when her plans escalate beyond her control. Her fragility and inflexibility are exposed by others’ criticism and judgement.

Maddy unwittingly criticises Emilie’s attempts to verbalise romantic sentiment when she dismisses her words as ‘frigid.’ Emilie is beset with further self questioning when she discovers that handyman Jean is, in fact a linguistic genius and multi decorated scholar of languages. Again both Maddy and Jean, who collectively exemplify the poetic true self, here serve to highlight the defence mechanisms which Emilie employs to bracket herself from all modes of exchange, whether it be verbal or amorous. Preoccupied with outward appearance, Emilie is unaccustomed to making herself vulnerable so it is perhaps ironic that her mother’s hapless and impulsive actions which drove her daughter to betray her heart, also teach her how to embrace and reciprocate love at the film’s denouement.

Deceit weaves through the script with some alacrity. At times, the film’s content seems a little overwhelming with ideas and nuances and delicious sub textual readings, however this all lends to a accumulative feeling of confusion and blurred, fluid forms which is exactly what the film is about. The lies communicated become the script’s bedrock of ideas, thus demonstrating the mutability of language and semiotics. The lies that the characters experience and make others experience, from the simple falsifications of a CV to fake love letters, an ex husband’s infidelity and ultimately the lies which we, like architects construct within ourselves , are all beautifully revealed within the film: the quest for the ‘real’ only evident via the written self.

The chicanes of language are presented as the plot’s fast paced twists and turns carry the audience along with the characters’ voyage of personal discovery and truth. This is an interesting idea which Salvadori reinforces through Emilie’s Greek travel brochures and Maddy’s discussion with Jean about her inspirational trips to Greece: the symbolic mother of philosophical thought and creativity. The personal quest for self knowledge evokes the epic voyage and tales of Ullyses as Maddy pointedly moisturises her hands as she speaks to Jean, suggesting further the theme of connection with the self through touch and creativity.

Messages exchanged via third parties are also a prevalent feature like the various ‘filters’ window panes, doors, letter boxes and voice mail which lead to a visual representation of a truth. The opening credits role with Jean, like a mythological Aescalus peering through stained glass, his object of desire Emile always out of his reach. The exchange of words and currency between Jean and Emilie regarding Maddy’s date with Jean are also delivered as two silhouettes behind a screen, witnessed by third parties Maddy and Sylvie the assistant. The impenetrable truth is played out before an audience who experiences the lie, who accesses the fact and yet does not interact with the performance, much like the activity of cinema itself: a projected sequence of reality rendered intangible to those outside it.

Beautiful Lies is a wonderful celebration of art which uses the mother-daughter symbiosis to untangle an equally complex relationship between art and reality. The inversion of roles and the interplay of truth and lie is brilliantly cultivated and exposed at the film’s end where we view the installation of an upturned olive tree. The tree of life and peace has been symbolically inverted, the roots exposed perhaps indicating an excavation of truth and nod to the foundations of language and communication. Similarly, the mother plays muse again and is hoisted up into the air by ropes as if taking flight into her new life, supported by the umbilical chords of creation.

A beautiful film which really serves to outline one of life’s most far reaching and examined questions about our relationship within the world we live, Beautiful Lies bursts with colour and shimmies with emotion – a beautiful lie which draws you in, involves, stirs and pulls tears and smiles from its audience. Leaving the cinema, you might emerge feeling enlightened, lucid even – perhaps that is the sign of a well crafted film when it interacts with its audience and affects your reality: the beauty lies within the cinematic experience of others.

Latest Posts

-

Film Trailers

/ 1 day agoM. Night Shyamalan’s ‘Trap’ trailer lands

Anew experience in the world of M. Night Shyamalan.

By Paul Heath -

Film News

/ 2 days agoFirst ‘Transformers One’ teaser trailer debuts IN SPACE!

The animated feature film is heading to cinemas this September.

By Paul Heath -

Film Reviews

/ 2 days ago‘Abigail’ review: Dirs. Matt Bettinelli-Olpin & Tyler Gillett (2024)

Matt Bettinelli-Olpin and Tyler Gillett direct this new horror/ heist hybrid.

By Awais Irfan -

Film Trailers

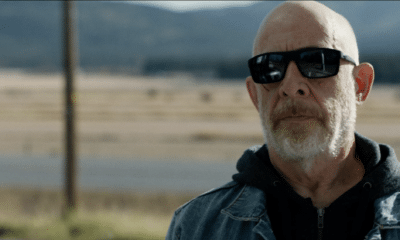

/ 2 days agoNew trailer for J.K. Simmons-led ‘You Can’t Run Forever’

A trailer has dropped for You Can’t Run Forever, a new thriller led by...

By Paul Heath